The following is a story that will be featured as a part of a series of interviews on perspectives of the environment by Trentonians. It will give Trentonians the opportunity to define their perspective of environmentalism. These interviews will serve as an archive for Trenton’s environmental story.

“We can’t make assumptions about how people interact with nature…We can’t assume that people who don’t commit to this work aren’t interested.” – William Wilson

“I’m always trying to tell my parents that they need to go out and do something besides work,” Jevon Lin told me. “They just sleep and work. To me a lot of Trenton is like that – sleep and work.”

Jevon Lin is a first-generation American. His parents have bounced around the states, first arriving in Minnesota and later New York, working as restaurant hands. They moved to Trenton over 11 years ago and opened their own restaurant. Jevon himself wears many hats around the restaurant.

Growing up, Jevon thrived in the structure and culture of school and work. “I did not pay attention to the world around me,” Lin told me. “Back then, I was pretty [self-centered]; focused only on my achievements.”

But then, COVID lockdowns took away the structure that Jevon thrived in. The bottom fell out for Lin, and he fell into a deep depression.

“Years of drowning myself in my work to escape my struggles left me isolated. I didn’t have any support system,” he told me. “I was locked inside all day, forced to face the problems I painted over for so many years.”

But Jevon wasn’t the only one who suffered. Trenton has a mental health crisis: about 1-in-4 people have/are suffering from poor mental health in NJ. This is a conservative estimate because most people aren’t focusing on their mental health; instead, they’re focusing on their work.

Lin argues that Trenton serves as a transition zone. It is a place where people go to earn money before moving on to better places. “No one is thinking about the world around them. It’s just ‘go to work and go to sleep.’ People in Trenton are struggling to make enough money so that they can have a better life, just like my parents,” Lin said.

Lin sees this routine of work and sleep building into a silent suffering, which forces most people to self-medicate with drugs like alcohol.

“One time there was this man in the restaurant,” Lin reflected. “I knew he was drunk, but he seemed in good spirits. After some time with himself while waiting on his food, though, I think that his struggles surfaced. When I brought out his food, his eyes locked with mine. I watched them fill with tears. His mother had passed away the day before. I thought about him a lot after he left. I prayed for his protection. I worried a lot about him and the people that depended on him, like the kids who [probably] now look to him. I really wanted him to come back to the restaurant one day so that I could share my own stories with him and share with him the truths I learned from God during my darkest moments – that men aren’t machines, that we need to acknowledge our mental health with one another. That isn’t possible in the world we live in, though. To me, Trenton has a lot of places to work, but few places to live. So, we suffer.”

For Lin, the process of getting out of his depression was a gradual one. He told me he found God during his darkest moments, “one night He came to me. That next morning, [when my mom opened the blinds], it was like a new light shined on me. In that light, I saw a tree, and that tree brought me peace.”

After lockdown was lifted, Lin took walks around his neighborhood. Whenever he found a tree, it brought him a sense of calm, of renewed peace.

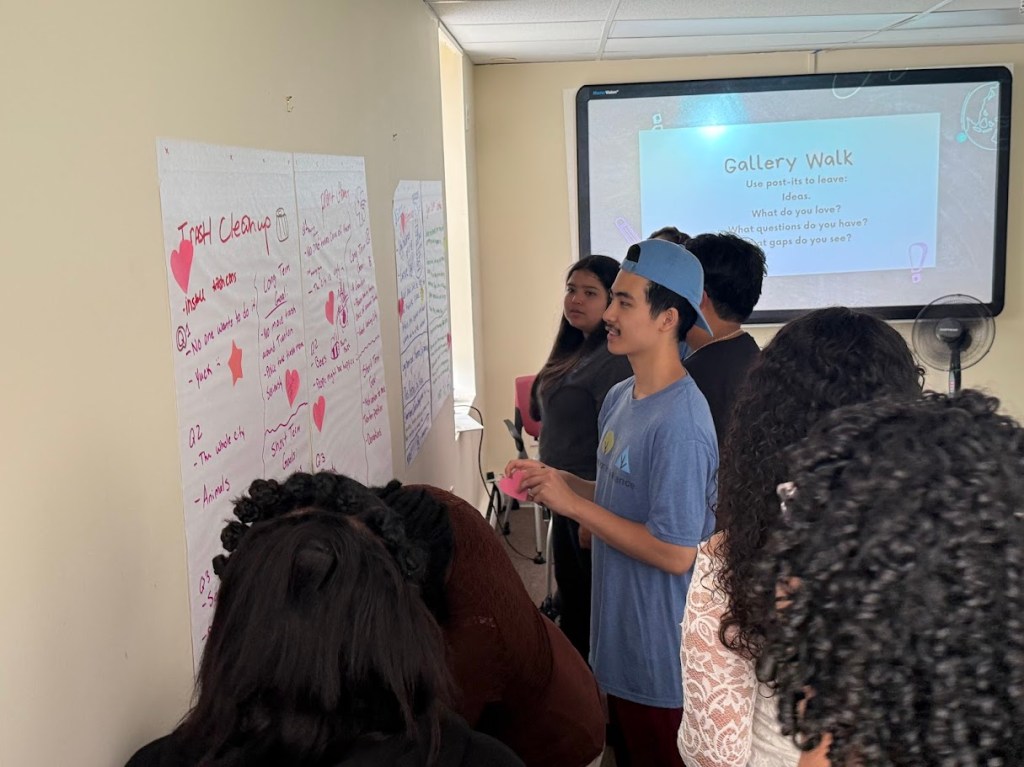

As school resumed, he joined a science-based mentorship program.

“Through that program, I visited my mentor once – it was the only time I visited her, but I immediately saw just how many trees Princeton had compared to Trenton. It was like another world,” Lin said. “In Trenton we don’t have trees like that, just stumps and buildings.”

I immediately saw just how many trees Princeton had compared to Trenton. It was like another world. In Trenton we don’t have trees like that, just stumps and buildings.”

Jevon Lin

Later, he joined the Trenton Tree Ambassador Program (TAP) through Mercer County Community College’s TRIO Upward Bound Program. Through TAP, Lin learned about the other benefits of trees beyond the mental health and spiritual benefits, “I learned that trees reduce stormwater and make the city cooler. I also learned that they’re a place where animals like birds live.”

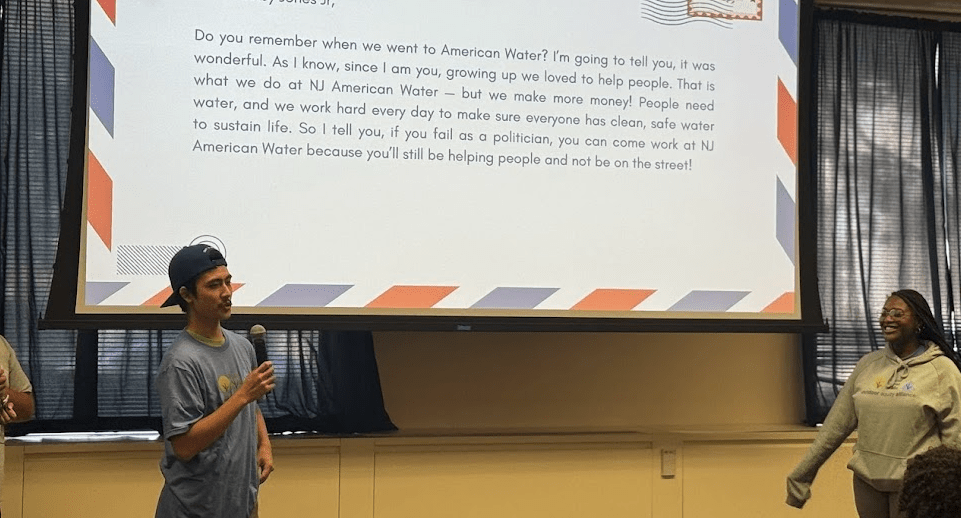

After high school Lin plans to go to college. He wants to study so that he can come back to Trenton and become a politician. “I want to help make Trenton into a place where people can live,” he told me.

“I want to help make Trenton into a place where people can live”

-Jevon Lin

For Lin, building a place where people can live means creating more spaces where community members can escape their struggles and reconnect with the calming benefits of nature in a clean and healthy environment. But to do that, he feels that we must remain committed to providing people work; just an alternative to the way we work today.

“Once, when I was at school, I saw this boy on the stairs sleeping,” Lin recounted. “He told me that he had only 2 hours of sleep the night before because he had to work.” To account for the fact that some students have to help provide for their families, Lin would like to see more opportunities for kids to work and earn a paycheck while developing skills they can use in a career dedicated to building green living spaces for people and our nonhuman kin.

Looking toward the future – his future and Trenton’s future – Lin told me, “I want to help build Trenton into a place where people can [root themselves], not just work to move on to the next place.”

-Harrison